Early treatment of sepsis remains a debate among health-care professionals. Four presenters in Antibiotics and Fluids: Controversies in Sepsis Care attempted to sway listeners and other panelists their way by presenting data and research on two critical aspects of early treatment.

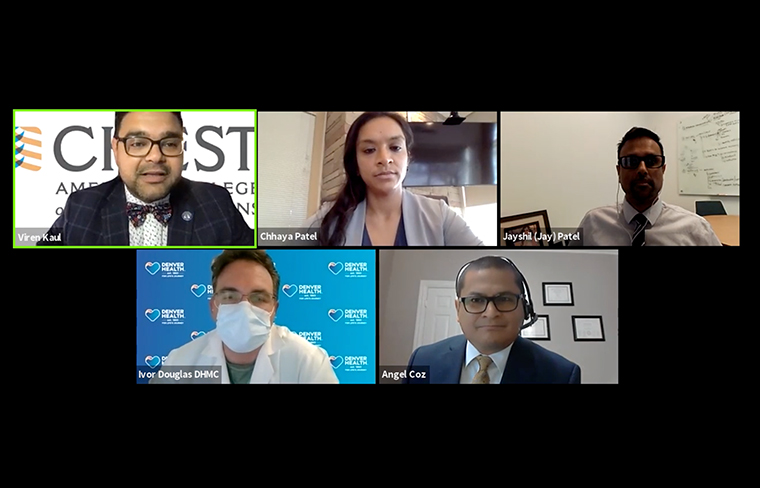

The first two presenters, Angel Coz, MD, FCCP, and Jayshil Patel, MD, argued whether everybody should receive broad spectrum antibiotics in the first hour or earlier. The last two presenters, Chhaya Patel, MD, and Ivor Douglas, MD, debated whether 30 mL/kg is an appropriate initial fluid bolus or if volume resuscitation should be tailored to the individual patient. The debate was moderated by Viren Kaul, MD.

Early Use of Broad-spectrum Antibiotics Saves Lives

Dr. Coz, MD, FCCP, associate professor of medicine at the Lexington VA Medical Center, tried to convince the panel that broad spectrum antibiotics should be used because “they do save lives,” but he emphasized that it’s not the same for every patient.

A study published in Critical Care Medicine in 2006 showed that the survival rate decreased every hour of delaying administration of antibiotics after the onset of hypotension. More contemporary data from New York, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2017, assessed about 50,000 patients, and again showed that, for every hour of delay, mortality went up by about 4%. A study from the University of Kansas showed that in patients with severe sepsis, the progression to septic shock was 8% more likely for every hour of delay in administration of antibiotics. Dr. Coz reminded everyone that stewardship is critical, however.

“If we don’t use broad spectrum antibiotics in our sickest patients, the ones who are the most vulnerable, then who are we saving them for?” He questioned. “Early antibiotics decreases mortality. Choosing the wrong antibiotics increases mortality. … When we have a septic patient or when we think about antibiotics, we need to think about, if it was my loved one, would I want to wait or would I rather give early broad spectrum antibiotics. Choose what is best.”

Maybe … But What About the Downsides?

Dr. Jayshil Patel, associate professor of medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin, countered Dr. Coz’s argument stating that broad spectrum antibiotics are not the right answer every time.

“I would contend that, before widespread policy is implemented, a course of action must demonstrate value,” he said, explaining that value equals quality plus outcomes divided by cost and/or harm. There’s less value with such an approach of broad-spectrum antibiotics to all patients. “Studies, while valid, don’t necessary have sound conclusions,” he said.

Observational studies demonstrate strong association between inappropriate antibiotics and worse clinical outcomes, but these observational studies are marred by heterogeneity, he explained. There’s different patient populations, different antimicrobial regimens, and different sources of infection, he said. And what do these studies have in common? He questioned. Their definition of appropriate—antibiotics has in vitro activity against the organism—and inappropriate—lacks in vitro activity.

“Furthermore, appropriate does not equal empiric broad spectrum for all,” he said. “Rather, antibiotic selection (in studies and at the bedside) has various meanings and depends on patient and local factors because no two patients, ICUs, communities are going to be alike. Therefore, empiric broad spectrum should be applied in the appropriate context and not as a ‘one-size-fits-all’ recommendation.”

30 mL/kg Is a Good Start for Patients With Sepsis

Dr. Chhaya Patel, division of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep at National Jewish Health, reviewed the Surviving Sepsis guidelines that recommend, in the resuscitation from sepsis-induced hypoperfusion, at least 30 mL/kg of IV crystalloid fluid be given within the first 3 hours.

“The fixed volume of fluid enables clinicians to initiate resuscitation while obtaining more specific information to essentially buy time in the process to figure out what’s going on with the patient,” Dr. Chhaya Patel said. “The idea potentially being that window of opportunity to give fluids can’t ever really go back in time to get that back.”

The study, Increased Fluid Administration in the First Three Hours of Sepsis Resuscitation Is Associated With Reduced Mortality, published in CHEST in 2014, looked at fluid administration in the first 3 hours, and survivors vs nonsurvivors at discharge.

“What they noticed was patients who got more fluid in the first 3 hours tended to have a higher survival rate,” she said.

Dr. Patel concluded with noting that, specifically for congestive heart failure, adequate fluid resuscitation is key, especially when the patient is particularly hypotensive.

Fluid Boluses Should Be Individually Tailored

Dr. Douglas, with the Denver Health Medical Center, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Anschutz Campus, wrapped up the conversation by strongly arguing that fluids need to be individualized instead of giving everyone the initial bolus, emphasizing that fluid imbalance can lead to serious consequences.

“Every patient has unique and constantly changing hemodynamic needs,” he said. “Understanding a patient’s volume status throughout their care is a challenge that clinicians face every day. Serious complications are associated with both under- and over-resuscitation, including organ failure and death.”

To view more details from each of the presentations, visit the CHEST virtual meeting platform.