It can be uncomfortable being in a space where you’re the only one like yourself, but “through our differences we grow,” said Nneka Sederstrom, PhD, MPH, MA, FCCP, during the Prejudice and Discrimination in Health Care panel at CHEST 2020. The session is available for viewing on the virtual CHEST 2020 meeting platform through February 1, 2021, for registered attendees.

“When we start to feel comfortable about otherness and being around people who are different and other than who we are, that opens us up to experiences that help us grow and develop,” said Dr. Sederstrom, director of clinical ethics at Children’s Hospitals and Clinics of Minnesota. “We have to work intentionally hard to remove the barriers that bias puts in our way and try and forge new paths in order to really truly stretch ourselves.”

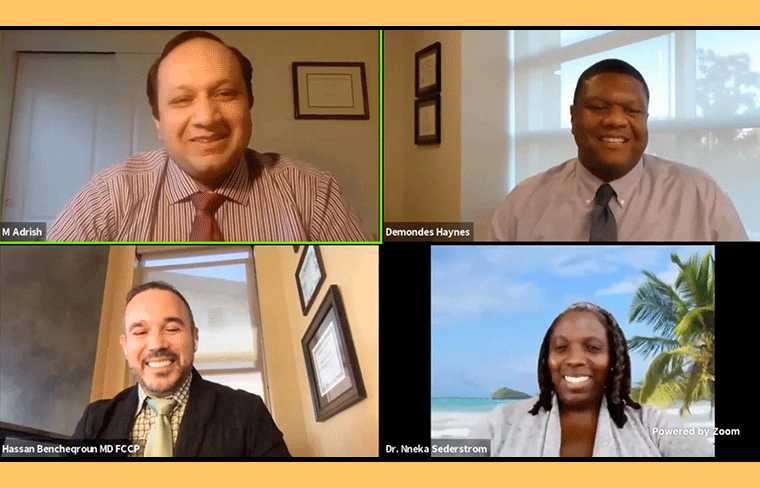

Panelists, including Dr. Sederstrom, Muhammad Adrish, MD, FCCP; Demondes Haynes, MD, FCCP; and Hassan Bencheqroun, MD, FCCP, addressed the importance of diversity and understanding other cultures, prejudices, and discrimination in health care and ways to overcome it.

Dr. Adrish, clinical assistant professor of medicine at Bronx Care Health System and Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, led off the session by defining stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination, which often lead to one another.

“Health care and inequality have gone hand and hand for many, many generations,” Dr. Adrish said. “It wasn’t until 1965 when hospitals were legally desegregated. Health is closely related to poverty, race, and housing. Therefore, we cannot address the health-care issues without first addressing these disparities in our health-care system.”

Following his talk, Dr. Sederstrom asked the panelists to think about their close friends and family, and their support system. “Are they the same or different from you and your family?” she questioned.

“We tend to, as humans, gravitate to like, and we tend to feel comfort in those who are like us,” she said. “When we try to pull people around us that are as close to family—the family we choose vs the family we are born in—we oftentimes forget that there’s power in privilege and stretching who our sphere of influencers are. Prioritizing the diversity in who we bring around us is a huge benefit to our children, immediate families, and by extension, to family members maybe we only talk to at Thanksgiving or Christmas, but it helps us be better people when we’re around them.”

Studies show increasing diversity within business and health care has a strong positive health effect on patients and outcomes, Dr. Sederstrom explained, pointing to a recent study that showed Black babies have a more positive outcome if their neonatologist is Black. And when you have a diverse environment, you create a higher morale for your employees—a place where they feel comfortable and heard, which leads to less burnout. Diversity also leads to better problem-solving and diversity of thought.

“When people come with different lenses, it’s such a rich conversation to be able to address a problem in a different way,” she said. “It opens up avenues that you may not have ever thought of before.”

The benefits of diversity are multifaceted, she continued, sharing how it allows for stronger advocacy for health disparities and community needs.

Dr. Haynes, pulmonary and critical care physician at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, emphasized the importance of cultural competency or the ability to understand, communicate effectively, and interact with people across cultures.

“We have to have the appreciation for these differences and for different cultures, and then gain some knowledge of the cultural practices, including other world views,” he said. “That becomes really important in health care.”

Dr. Haynes shared a learning and teaching moment where he educated a fellow about a transgender patient and their culture.

“If you don’t understand, it is incumbent upon us to learn,” he said about cultures. “It goes back to that cultural competency thing. There’s no way any of us can learn and know everything about different cultures. There’s so many, but you have to put forth the effort, and it’s your job as the physician or provider, or if you’re an APP or another clinician, to have that rapport with your patients. That’s part of medicine. Developing rapport with patients goes beyond treating conditions.”

Physicians also tend to not spend as much time trying to educate Black patients as opposed to white patients, he said, emphasizing how physicians need to spend more time listening to these patients and educating them.

Dr. Bencheqroun, a pulmonary and critical care physician in San Diego, addressed the various microaggressions different groups of people face, whether you’re a woman and someone says “If a girl can do it, so can I” or “Could you run and get my nurse please?” Dr. Bencheqroun showed a powerful photo of a diverse group of people showing various signs. One said, “Muslims are not all terrorists.” Another said, “I am not a color.”

“These are the assumptions that are made—and how it makes its way into patient care and into our societies. We should come up with intentional revision of whatever we’re doing to include race, religion, and ethnicity.”

For example, during Ramadan, it’s a fasting period between sunrise and sunset, which means during that time Muslims cannot take any medication. One way to accommodate that would be taking an extra step to learn about the pharmacodynamics of the medication and come up with a different time or plan to take that medication during Ramadan.