It wasn’t long ago that COPD was considered an irreversible condition with limited treatment options and few good outcomes. Two decades of intensive research has dramatically expanded treatment options and outcomes.

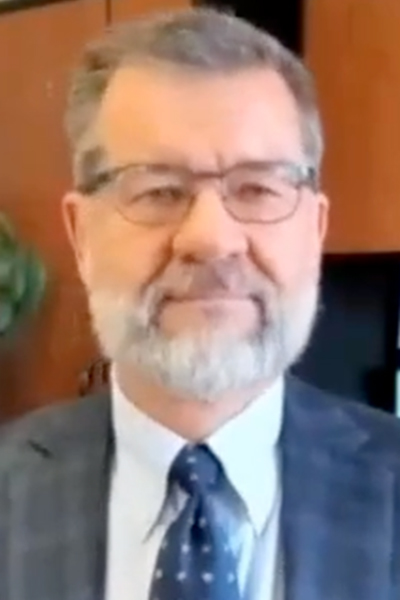

“The pathology of COPD may not have changed much over time, but today we can do a lot to reverse the important disabilities from the patient perspective,” said Darcy Marciniuk, MD, Master FCCP, professor of respirology, critical care, and sleep medicine at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada.

Dr. Marciniuk explored the transition of COPD from death sentence to manageable respiratory condition during the Presidential Honor Lecture “COPD Management: We’ve Come So Far.” The session recordings are available for viewing on the virtual CHEST 2020 meeting platform through January 18, 2021, for registered attendees.

When he began training, Dr. Marciniuk remembered, clinicians didn’t even have a common name for what is now known as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Symptoms were diagnosed as emphysema, chronic bronchitis, asthmatic bronchitis, chronic airflow limitation, and other confusing terms that were not discarded until the late 1990s.

Treatment was sketchy at best and risky for most patients. The only single metered dose inhaler available required 16 to 32 puffs per day. Systemic corticosteroids were the standard maintenance therapy and almost every patient was on theophylline and aminophylline.

“While these treatments worked, the risk-benefit ratio was very much on the risk side,” he said. “Now we have much safer, much more effective pharmacologic agents than ever before.”

Milestones in the treatment of COPD abound. The discontinuation of intermittent positive pressure breathing to deliver bronchodilators, the introduction of antibiotic therapy to enhance recovery from COPD exacerbations, recognition of the benefits of smoking cessation on survival, and the introduction of lung transplantation all improved outcomes. But COPD death rates continued to climb.

While the death rates for stroke, heart disease, accidents, and cancer declined between 1970 and 2002, the death rate for COPD climbed by 102.8%. COPD is now the third leading cause of death globally.

“Our understanding, our appreciation of just what COPD is doing has shifted in the last 15 years,” Dr. Marciniuk said. “We have recognized and are accepting the burden and magnitude of COPD. We have much more effective bronchodilators and other therapies, alone and in combination. And we have meaningful targets for those therapies.”

Pulmonary rehabilitation has shifted from the inpatient setting, where it can be effective but costly with temporary benefits, to long-term maintenance rehab in outpatient settings. Clinical practice guidelines now focus on targeted therapies for the prevention of acute exacerbations, which are a gateway to reduced lung function, reduced quality of life, increased ED visits, increased hospitalizations, and increased mortality.

Simply adding pulmonary rehabilitation to bronchodilation can more than double mean walking distance over at least 24 months, Dr. Marciniuk noted. Pulmonary rehab can produce similarly striking improvements in anxiety and depression, both risk factors for poor long-term outcomes.

An analysis of Medicare claims data found that implementing pulmonary rehab following hospitalization for acute exacerbations can reduce 3-year mortality by 37%. But only 2.8% of patients hospitalized for acute exacerbations actually initiate pulmonary rehab.

The number, type, and effectiveness of COPD medications has increased dramatically in recent years. Clinicians have largely accepted the superiority of dual therapy over monotherapy. Triple therapy can provide even greater benefits in select patient populations.

So can nonpharmacologic therapies such as endobronchial valves and noninvasive ventilation.

“Our understanding of COPD, and the diagnosis and management of COPD, has changed significantly for the better over the years,” Dr. Marciniuk said. “We can genuinely improve lung function and quality of life, enhance activity and exercise performance, and reduce exacerbations, hospitalizations, and health-care utilization for our patients. But there is still so much to do.”