Point-of-care ultrasonography (POCUS) can save time and limit patient exposure to ionizing radiation and intrahospital transport for critically ill patients, yet the evidence to support its use in the ICU remains inconclusive.

In the Monday session POCUS Controversies in the ICU, experts addressed the advantages and pitfalls of diaphragm ultrasound and venous excess ultrasound (VExUS).

Diaphragm ultrasound

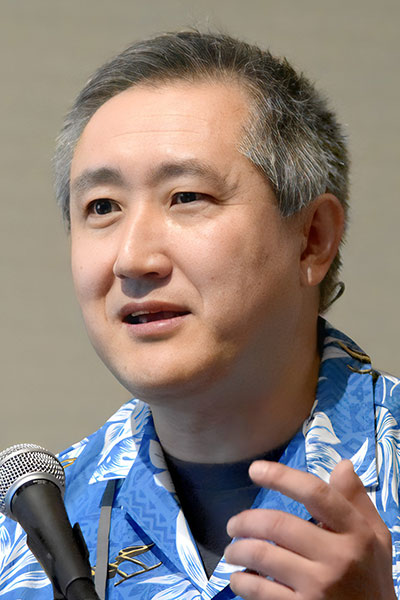

Taro Minami, MD, FCCP, and Michel Boivin, MD, FCCP, took opposing stances on the benefits of diaphragm ultrasound in mechanical ventilator weaning.

“It’s an accurate way to assess the diaphragm functions, and it is easy to perform,” said Dr. Minami, Associate Professor of Medicine and of Medical Science at The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, and Director of the ICU and Director of Medical Simulation and Point-of-Care Ultrasound Training, Kent Hospital and Care New England.

Research at the Mayo Clinic has shown that diaphragm ultrasound, which is noninvasive, can detect chronic nerve dysfunctions with a sensitivity of 93%, he said, adding that specificity is also quite high.

Dr. Boivin, Professor of Medicine, University of New Mexico, acknowledged that there are multiple recognized benefits for diaphragm ultrasound. It is the most effective test to monitor diaphragm function in the ICU, and diaphragm dysfunction is an underrecognized cause of extubation failure, he said. Further, delays in extubation are associated with poorer outcomes. Re-intubation is associated with even worse outcomes.

However, diaphragm ultrasound is time-consuming and its success is highly operator-dependent, Dr. Boivin pointed out. Studies on the benefits of diaphragm ultrasound have not been large enough to provide sufficient data to support widespread use of this imaging.

In one randomized trial of 30 patients on prolonged ventilation, information from the diaphragm ultrasound was given to the clinicians in half of the cases.

“What they found was that if you gave the treating teams the information that the diaphragm ultrasound was good and told them that they had a 90% chance of success, they extubated [the patient] faster,” Dr. Boivin explained. “But the thing I didn’t understand is that when they gave them the information that the diaphragm ultrasound was bad, they also extubated them faster.”

Amid this puzzling parallel is a significant takeaway, he said.

“I think the important thing is that they’re on the right track here, that we need to systematically do studies that involve giving people the prospective information and see if we can get better outcomes,” Dr. Boivin said.

Venous excess ultrasound (VExUS)

Navitha Ramesh, MD, MBBS, FCCP, and Abhilash Koratala, MD, provided data to demystify VExUS and make the case for incorporating this advanced imaging into day-to-day practice in the ICU or nephrology.

VExUS quantifies the severity of venous congestion of the inferior vena cava, liver, gut, and kidneys.

“The potential value that I see in VExUS is serving as an early warning sign for stopping further fluid therapy,” said Dr. Ramesh, Critical Care Medicine Fellowship Program Director at University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Harrisburg. “Signs of congestion in multiple solid organs can give a much stronger picture or prediction of higher risk of potential harm with additional fluid therapy.”

One limitation of VExUS is that it does not identify the source of venous congestion, and Dr. Ramesh recommends it not be used exclusively but rather as an adjunct.

However, the waveforms of VExUS do help monitor the efficacy of decongestive therapy in real time, said Dr. Koratala, Associate Professor of Medicine and Director of Clinical Imaging, Division of Nephrology, Medical College of Wisconsin.

“VExUS does not distinguish between volume and pressure overload,” he said, adding that organs likely don’t behave differently based on whether the organ congestion is caused by pulmonary hypertension or fluid overload.

“You just you have to take into consideration the clinical context and do for the patient whatever is appropriate—diuretics or dialysis or pulmonary vasodilation or lung transplant, heart transplant, whatever is appropriate,” Dr. Koratala said.