Burnout is often called a plague among critical care clinicians because it is so easily transmitted from clinician to clinician. In reality, it is an environmental hazard in the health-care workplace. Simply recognizing burnout as an occupational hazard changes the conversation.

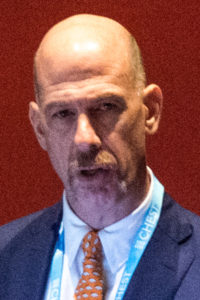

“If ICU physicians were coal miners, the onus of correcting occupational hazards would lie with the employer,” said Marc Moss, MD, Roger S. Mitchell Professor of Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. “In medicine, the onus still lies with the individual. That needs to change.”

Dr. Moss spoke at the Sunday session Extinguishing ICU Burnout: An Interactive Session Focusing on Recognizing, Preventing, and Managing Burnout.

The Critical Care Societies Collaborative (CCSC), which includes CHEST, the American Association of Critical Care Nurses (AACCN), American Thoracic Society, and the Society of Critical Care Medicine, issued a call to action to combat burnout syndrome in 2016.

“Physician and nurse suicide numbers are mind blowing,” said former AACCN president Vicki Good, DNP, Rn, CENP, CPPS. “We need to break the culture of silence that leaves clinicians feeling that they are alone.”

The CCSC noted that mitigating the development of burnout in critical care health professionals is not just good for clinicians. Reducing burnout is also good for patient care and for institutions.

The typical hospital spends about $500,000 to replace an ICU physician, Dr. Moss explained. Annual ICU turnover due to burnout is about 3%. That means a moderate-sized department of medicine with 450 physicians is spending $6.75 million annually just to replace burned out physicians.

The typical mid-sized ICU spends another $1 million annually to replace nurses who leave due to burnout.

“That should get attention from your chief financial officer,” Dr. Moss said. “We can save a lot of money by reducing burnout and lowering turnover.”

Most CHEST members probably have seen burnout numbers, noted Curtis N. Sessler, MD, FCCP, Orhan Muren Distinguished Professor of Medicine and director of the Center for Adult Critical Care at Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine. More than a third of ICU physicians labeled themselves burned out in a recent survey, and nearly 60% admitted to being unsatisfied with their work-life balance.

He polled the session audience survey, finding that 46% had mild burnout, 38% had moderate burnout and 3% had severe burnout.

Institutions and practices are not helping. Although 87% of attendees had some degree of burnout, 47% said their institutions did a poor job dealing with burnout. Another 37% gave their institutions a fair grade.

“Do institutions and practices even recognize burnout?” Dr. Sessler questioned. “Our institutions are not doing much. We are doing better, and we all have opportunities.”

Multiple stakeholders are developing strategies to mitigate burnout by reducing workplace stresses and giving clinicians new tools to reduce burnout by building their own resilience.

The American Medical Association’s Steps Forward program includes multiple modules that focus on workplace changes, including steps to prevent burnout. The American Psychological Association has its own six-step plan to avoid burnout.

“Resilience is not a trait,” said Ruth M. Kleinpell, PhD, RN, professor of adult health and gerontological nursing at the Rush University College of Nursing. “It is behaviors, thoughts, and actions that can be learned. You can’t change the fact that crisis happens, but you can change the way you react to it.”

Failure is a major stressor for most clinicians, she noted. But failure is also valuable feedback. Every failure provides a clearer path to move forward the next time.

“Resilience is a shell we can build in ourselves and in our workplaces,” she said.